When I was a doctoral candidate struggling to get my dissertation proposal approved, I was confused about what exactly I should propose as my research plan. I knew what my topic was, but I needed to be a lot more specific, and I also needed to justify every item on my plan. Where to start?

I read several of Creswell’s research design books and got even more confused. So many choices! So many terms that seem to mean the same thing but apparently don’t … words like approach, worldview, paradigm, theory, method, design, strategy, technique, tactic … it’s enough to make a poor dissertator insane.

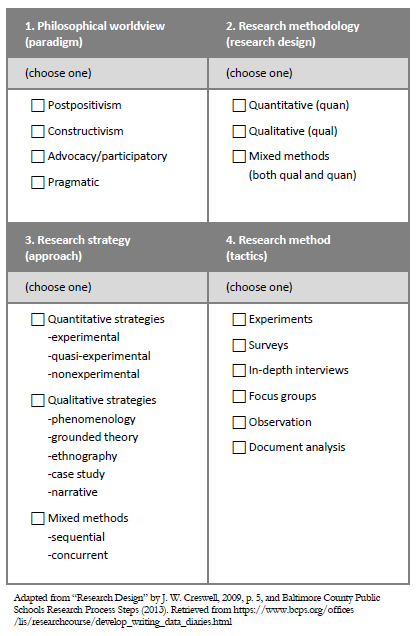

The chart shows four quadrants with a buffet of choices. Quadrant 1 shows some “worldviews.” Quadrant 2 shows some methodologies (research designs). Quadrant 3 shows some research strategies (approaches), and Quadrant 4 shows a list of methods (tactics). For best results, choose ONE element from each quadrant.

When I was a dissertator, I assumed I was supposed to work through these elements in sequential order; I saw the word worldview and immediately froze in terror. It took me a long time to get past that first quadrant.

In the following paragraphs, I offer a slightly different approach, based on my experience and the experiences of other dissertators whose papers I have edited. Maybe this simplified approach to choosing your research methodology and method will help you quickly get your proposal approved so you can start the fun part of your dissertation journey—collecting your data!

Quadrant 1. First, according to Creswell (2009), we have to identify our overall approach—our worldview. Are you a postpositivist researcher? Are you a constructionist? Are you all about participation and advocacy? Or are you a down-to-earth pragmatist? What does all that even mean?

Quadrant 2. Next, we are required to choose a methodology. Methodology is the overall research design. You have three methodological options: quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods (which is a combination of qualitative and quantitative). You might be perplexed: Should you do a quantitative study (focused on numbers), a qualitative study (focused on words or images), or should you do both (mixed methods)? You have to choose one. How should you make that important decision?

Quadrant 3. Within each methodology, we are also expected to choose some sort of approach or strategy. For example, if you chose a quantitative methodology, you have to decide between experimental, quasi-experimental, or non-experimental approaches. Which one would be best for your study? If you chose a qualitative methodology, you could select from five classic strategies: phenomenological, ethnography, narrative, case study, or grounded theory. (I know—I was like, what? What bizarre buffet did I just accidentally get invited to? I don’t speak this language!)

Quadrant 4. Finally, we must choose our research method—the actual tactic we will employ to collect data. Should you collect primary data or use secondary data? If you collect our own data, should you survey people? Would you interview people? Would you observe people? Some combination of these tactics? So many choices! Should you just close your eyes and throw a dart? Should you consult a psychic or an astrologer? Are the planets properly aligned? Maybe the Magic 8 Ball has the answer.

Nope, apparently not. What is a frustrated, confused dissertator to do?

Start with Quadrant 4

Instead of taking the quadrants in order one at a time, from Quadrant 1 through Quadrant 4, I suggest you consider starting with the methods (tactics) in Quadrant 4. This strategy worked well for me. I had no clue what my philosophical research worldview should be, but I knew that I needed to talk to people about my research topic. That meant conducting some interviews.

Method is the way we conduct our research. Method encompasses the what, who, where, and when of the study. The tactics are the blueprint for your study. Now, practically speaking, how are you going to get ahold of some data? You have essentially three choices. You can survey people, you can talk to people, or you can observe people, or any combination thereof. For example, you might survey a group of people before and after an event. Or you could interview people about their perceptions of the event. Or you could observe people’s behaviors during the event. Or you could do all of the above.

Now consider Quadrant 2

Once you choose your tactical-level method, it easy to determine which overall research methodology encompasses your method. If you are talking to people, that will likely generate text data—in other words, words—and that is by definition a classic qualitative methodology. In contrast, if you are sending out a survey that requires respondents to click numbers to indicate their level of agreement with some statements, that method will generate numerical data, which by definition is a classic quantitative study. If you have a combination of both words and numbers, then you have chosen a mixed-methods methodology.

Which one should you use, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method? The correct answer is, whichever one answers your research question most effectively. Are you really asking, which one is easier? That depends. Are you a number person or a word person? Do you want to challenge yourself, or do you just need to get this thing done? Are you wondering which methodology is faster? Quantitative, usually.

Now you are ready for Quadrant 3

Now that you know your research methodology, you can determine which subcategory from Quadrant 3 is most relevant for your study. Quadrant 3 is a refinement of your methodology choice from Quadrant 2. Your choice of methodology is important, because it leads logically to your method—and vice versa. They need to align logically. You can’t proclaim your intention to use a survey to collect numerical data and then call that a qualitative methodology. Likewise, you can’t say you are going to conduct interviews and call that quantitative. According to Creswell (2009), you have five traditional options for qualitative methodology and three main options for quantitative. Remember, the best choice is the one that best answers your research questions.

Back to Quadrant 1

Finally, we come back to Quadrant 1. What is all this stuff about worldviews or paradigms? What is a philosophical worldview? That question is not too hard to answer: A worldview is a mindset, a basic set of beliefs or assumptions about how things are. A way of thinking about things. Like Republican versus Democrat, sort of, but less fraught.

The worldview we choose provides the philosophical foundation for the strategy and methods we will use for our research. Using Creswell (2009) as our guide, we have four choices when it comes to worldviews or paradigms: Post-positivism, constructivism, advocacy/participatory, and pragmatist. It should (eventually) become apparent to you that the first term in Quadrant 1, postpositivism, usually refers to quantitative ways of finding out stuff, and constructivism usually refers to qualitative ways of finding out stuff. That is a simplification, but for our purpose, it works.

Odds are your project will be one of these two worldviews. However, it’s best to choose your worldview based on the research problem you have identified. So, for example, if you plan on getting down and dirty with your data, like going undercover into A.A. meetings to find out how the members manage to “govern” their organization with no bosses, or interviewing LGBTQ teens with a goal of helping schools build inclusive communities, then the advocacy/participatory paradigm is the worldview for you.

The fourth worldview, pragmatist, is a smorgasbord hodgepodge of whatever you want it to be. I recommend you steer clear of this worldview—it’s difficult to pin down, because it can encompass just about any approach you can cook up, and reviewers won’t understand it. You’ll waste a lot of time defending your choice.

Dissertators sometimes want to implement the most complex study they can, as if that will prove something. You don’t have to prove anything. I encourage you to keep it simple from the beginning. If you want to get your proposal approved in the least amount of time, go with what works: either postpositivism (quantitative) or constructivism (qualitative), depending on your research problem and your propensity toward numbers versus words.

Now you’ve covered all four quadrants, from general to specific. Make the easier choices first—tactics and methodology, and then work your way to the approach and worldview, using peer-reviewed guidance gleaned from the literature in your field. With these research elements in place, you’ll soon get your dissertation proposal approved and be on your way to collecting data.

Reference

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.