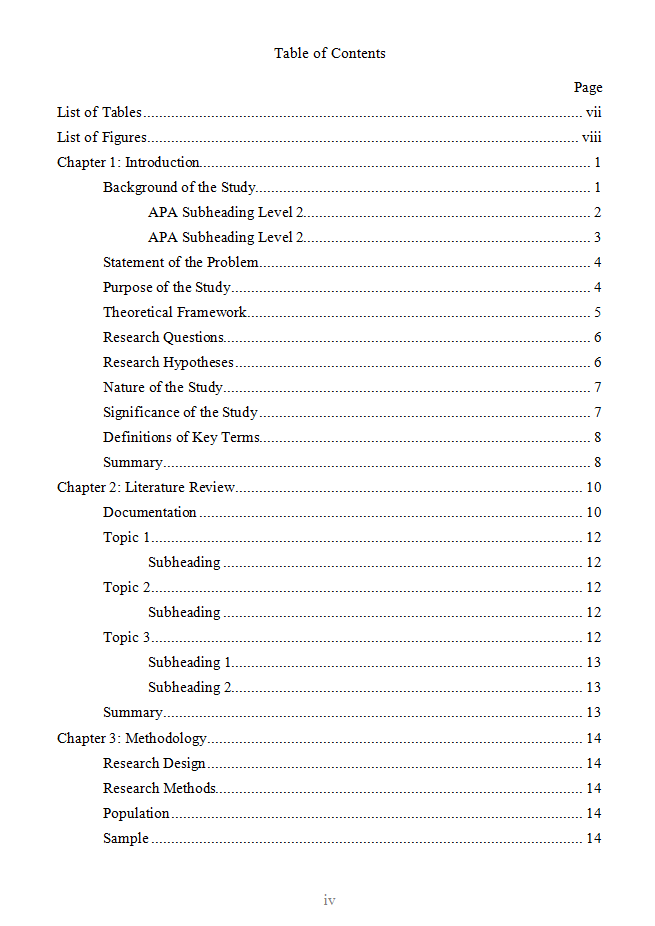

In Part I, I discussed all the gobbledegook (technical term) that goes into the front matter of your dissertation proposal. In Part II, I describe the elements of the first chapter of a typical three-chapter proposal. I know what you’re thinking: What could be more fun?

The dissertation proposal: Chapter 1

Chapter 1 is the introduction to your study—you already know that much, I bet. A typical Chapter 1 contains the background, problem, purpose, research questions, maybe the significance of the study, a brief overview of your research plan, and a list of definitions of key terms.

Whew! A lot of stuff goes in Chapter 1. That makes sense. It’s an overview of your entire proposal, after all. What can go wrong? Plenty.

For best results, write Chapter 1 after you have written Chapters 2 and 3. Does anyone actually do that? I am positive many dissertations do not, judging by how what they write in Chapter 3 fails to align with what they wrote in Chapter 1. It’s like dissertation amnesia sets in somewhere in the middle of Chapter 2. Suddenly they forget they were planning a qualitative study and start waxing eloquently on the challenges of using probability methods to choose a sample size. Hooboy. Amnesia!

What elements belong in Chapter 1? Let’s briefly talk about each one, just to make sure we are on the same page.

Introduction. The first section if Chapter 1 is the introduction (duh), although according to APA style, we omit the “Introduction” heading, because I guess everyone knows the first paragraphs of a chapter constitute the introduction to the chapter. Thus, adding the heading is unnecessary. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve written that exact message in a comment box in someone’s dissertation—I can tell you, it’s a lot. This very common error is attributable to failure to read that pesky style manual. Come on, social science dissertators! Read your style manual.

The introduction to the chapter is not an overview of the study; it’s an introduction to the topic. I recommend writing the Background and Problem Statements before you write this section. The introduction is the setup. If you “preview” the main points that lead to the problem your study will address, your readers will be deeply comforted. Your reviewers will feel reassured (and more likely to approve your proposal) if your preview aligns with your background and problem statement sections.

Background. Often, the next section will have a subheading, “Background.” Write Chapter 2 first (Chapter 2 is usually your literature review); then you can copy and paste a few of the highlights here. I mean, copy a few sentences, the pithy ones that neatly summarize the situation. Don’t copy entire paragraphs! Reviewers really dislike reading the same material twice. Except for the elements that have to be consistent between chapters, I mean. Like your problem statement, your purpose statement, and your research questions. Gah! Did I just make things more confusing?

Problem statement. The problem statement should be one concise (250-300 word) paragraph stating explicitly the problem your study will address. Don’t pussyfoot around, don’t make your readers try to guess the problem from your eloquent pleading. Just say it: “The problem addressed in this study is…” Some institutions will have you state the general problem (the broad problem) and then state the specific problem YOUR study will address. For example, “The general problem addressed in this study is that dissertators cry a lot during the proposal-writing process. The specific problem addressed in this study is whether dissertators’ moods (measured on the Dissertator Mood Scale) correlate with how many times they submitted their proposals before receiving approval.”

Purpose statement. The purpose statement should clearly flow from the problem statement. Some experts recommend using the exact wording from the problem statement in the first line of the purpose statement (or as close as possible). For example, “The purpose of this study is to determine to what extent dissertators’ moods (measured on the Dissertator Mood Scale) correlate with how many times they submitted their proposals before receiving approval.”

The rest of the purpose statement should contain descriptions of the study’s implementation: the population and sample, the sample size, the recruiting method, the data collection and analysis methods, and the geographical area. Just lay it all out there. Quite often, the purpose statement is one paragraph, but generally does not exceed one page in length.

Theoretical (or conceptual) framework. For all you folks aiming at earning a Ph.D., this section is vitally important. To earn your degree, you must extend theory, not just apply it. If you are seeking some other type of doctorate, like a D.B.A. or Ed.D., you may not have to extend theory, but you still need some sort of explanation of what worldview you are using to organize your study.

That is why I am astounded that dissertators sometimes leave the theoretical framework section out entirely. Without some sort of theoretical or conceptual framework, your study has no bones. What would happen if your skeleton suddenly disappeared? Right. Like that. Not good.

What theory could explain why dissertators get more and more depressed as they keep submitting their proposals and receiving rejections? (I feel I can speak on this topic, having been one of those demoralized dissertators.) Maybe it’s because of attribution theory, or motivation theory, or even discomfort theory. If you have done your homework (read many articles and dissertations), then you know the theories that are relevant to your topic. You can try to debunk them, extend them, confirm them… you can even make up one of your own! But you Ph.D. wannabes gotta have a theory.

Some of you qualitative folks might not use an actual theory. Instead, your institution may require you to propose a “conceptual framework.” This kind of framework might not rise to the level of being an actual identifiable theory (although it might someday, thanks to your research), but it should offer the reader some explanation of why you think the phenomenon is happening. Are dissertators just a bunch of whiners? Could be. More likely, dissertators get discouraged when they don’t achieve their desired outcome. That could be your conceptual framework. Your research will explore, expand, confirm, or disconfirm that statement.

Research questions. Now that you know the problem, the purpose, and the theoretical framework you will use, you can write your research questions to align with those elements. Your goal is to make sure these elements are all aligned—that is, that they make sense in relation to one another, creating a logical flow, from problem, to purpose, to questions. The problem is XYZ, so my purpose will be to investigate XYZ, and therefore, my research questions will be logically aimed at resolving XYZ.

Right. Clear as mud? Well, aligning the elements of the proposal is by far the hardest part of the project. Don’t freak out—we all have to go through it. However, once you get all the pieces lined up, everything will suddenly fall into place. It’s a great feeling.

Nature of study. The nature of the study section might be a few paragraphs or several pages describing in more detail how you plan to implement your study. Specifically. I mean, truly nuts-and-bolts specific. It’s a distillation of Chapter 3—write Chapter 3 first, so you can pluck statements to describe the population and sample and explain how you plan to recruit participants. Describe your data collection and analysis plans in some detail, more than you wrote in your Purpose Statement, but much less material than you will write for Chapter 3. Don’t let this section be more detailed than your discussion in Chapter 3! That happens. Don’t do it.

Significance of study. The significance of your study rests on how well you can justify its approval. What will happen if we don’t get the benefit of the results of your study? Who will be harmed? What happens if you conduct your study? Who will be helped?

Social science dissertators seem to like to wax maudlin in their problem and purpose statements. That means they use frothy overly dramatic arguments to convince the reader that the problem they have identified is worth studying. I’m sorry to tell you, the frothy emotional appeal is not a sound justification for your study. Your best bet is to cite some previous experts in the field who recommended some future researcher (you, for instance) should study dissertators’ moods. If credible, peer-reviewed researchers say something needs to be studied, then you can feel confident you have a solid justification for your study.

Definitions of key terms. Usually, Chapter 1 closes with a list of definitions, arranged in alphabetical order, with citations. Don’t overdo it. You won’t need definitions of terms like dissertation, quantitative, or survey. Mostly, you should aim to define a key term the first time you mention it. Most of your readers won’t go back to your list of definitions to look something up—they’ll just flail along hoping it will all soon make sense. That is not what you want. Make it easy on your reader and provide all the help you can as they are reading, so they never have to stop and wonder, what the heck does that word mean?

Oh, yeah, one more thing. Whatever terms you decide to use, use them consistently throughout your paper. This isn’t creative writing, people. Take pity on your readers (and reviewers). Be consistent.

Next time, I’ll write about Chapter 2, traditionally the review of your literature. What could possibly go wrong? A few things. Stay tuned.

I’ve written the book I wished I had had when I was sweating over my proposal, watching the clock ticking and thinking, hmmmm, failure is apparently an option after all. I wanted simple, practical advice from someone who had been in my shoes, someone who didn’t throw more academic jargon at me, but shared real stories to give me insight into the obstacles that were holding me back. I wrote the book I didn’t have when I could have really used the help.

I’ve written the book I wished I had had when I was sweating over my proposal, watching the clock ticking and thinking, hmmmm, failure is apparently an option after all. I wanted simple, practical advice from someone who had been in my shoes, someone who didn’t throw more academic jargon at me, but shared real stories to give me insight into the obstacles that were holding me back. I wrote the book I didn’t have when I could have really used the help.