I can come up with a gajillion excuses why I can’t. Can’t what, you say? Can’t anything. Ask my mother, I bet she will say I was born moaning “I can’t!” Usually the thing I think I can’t do requires things I think I don’t have—typically, time, money, or energy. Rarely is the problem as simple as I don’t know how. Almost always, I’m bound up by my fear that I will fail. Here’s what to do when you are struck with a case of the “I can’ts” as you are struggling to get your dissertation proposal approved.

I can’t [fill in the blank]

When I was working on my doctorate, my sad refrain to my long-suffering colleagues was “Woe is me, I can’t finish this monstrosity!” While I was writing my first book, I whined frequently “I’ll never get it done!” to anyone who would stand still long enough to listen. I seem to be genetically disposed to complaining that I can’t do something, when the evidence implies otherwise.

The fact is, I did finish my doctorate. I did write that book. I can’t very well point to my track record and say, “See, Carol? You didn’t . . . so you can’t.” Because I did. So clearly, I can. If you get my drift. I confess, I was a Negatron long before there was such a thing. The good news is, it doesn’t matter! Let me repeat: positive attitude or negative attitude, or anywhere in between—it doesn’t matter.

Confidence is nice but not essential

You may be an expert on the power of positive thinking. If so, yay for you. If you don’t tend to look on the bright side, welcome to the club! The good news is, you don’t have to. Confidence is nice but not essential to completing your proposal. All the confidence on the planet is not going to earn approval if your grammar is subpar or you are missing critical citations. Just saying. In fact, I think confidence might be overrated. Confidence can become arrogance in a heartbeat. Arrogance can lead us to assume that our work is stellar when really it’s a big hairy mess.

Some people are naturally confident. I’m not one of them. Lacking natural confidence might sometimes be a good thing. For example, if I were naturally confident, I might say something breezily self-centered like “Feel your fear and do it anyway!” I might say “Go boldly in the direction of your dreams” without noticing you are hiding under the covers. I might say “Hey, all you have to fear is fear itself.” Blah blah blah. But I’m not naturally confident. I’m naturally terrified. You can diagnose me with low self-esteem, personality disorder, whatever. I’m here to tell you, none of that matters. I lack confidence, and I still earned my doctorate—it can be done!

There were times in my 8-year doctoral journey that I seriously doubted my ability to perform to a high enough standard to achieve my dream. When things got intense (meaning, when I was terrified out of my wits that I would fail), I narrowed my focus to the tiny piece of action in front of me: the chapter, the paragraph, the sentence. After I typed each sentence, I stopped to make sure what I was writing was on track and in alignment with my overall purpose and plan.

Sometimes I was too scared to write. Naptime! Right up until the end of the defense, I lacked confidence. As I wrote my book, I lacked confidence. As I write this blogpost, I lack confidence! Argh! However, if you are reading these words, I rest my case!

Action is the magic word

Lately my plaintive cry is “Alas, I can’t be creative. I can’t be successful. I can’t be successful being creative.” It is so much easier to complain about how my dreams daily fail to materialize . . . while ignoring the embarrassing fact that I’m doing practically nothing to help them happen. I spend a lot of time dreaming and fretting and not much time doing. (I can’t because . . . )

What do you worry about? Probably we worry about similar things. Here are a few of my worries: My work isn’t good enough. My topic is stupid. It’s been done. It’s already obsolete. It’s incoherent gibberish. I’ll never get done. This is costing me a fortune. I usually finish up with something like Alas, alackaday, woe is me [place back of hand on forehead].

We don’t need positive thinking, and we can’t sit around doing nothing. It’s all about action, people. Any action. You don’t have to believe in it, you just have to do it (obligatory kudos to Nike’s tagline, forever embedded in the American zeitgeist). It doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to get done. This isn’t the culmination of your career, it’s just the beginning. You have lots and lots of road ahead of you to get it right.

Some words on the paper is better than zero words, even if they are incoherent gibberish. That’s how this blogpost came to be. Bla bla bladdy bla and next thing I know, I’ve got something done. Not perfect. Who cares. Sometimes, yes, the good is the enemy of the best, but perfectionism is the enemy of good enough. Nobody gets it right all the time. The ones who win (you define winning) are the ones who don’t quit, no matter what.

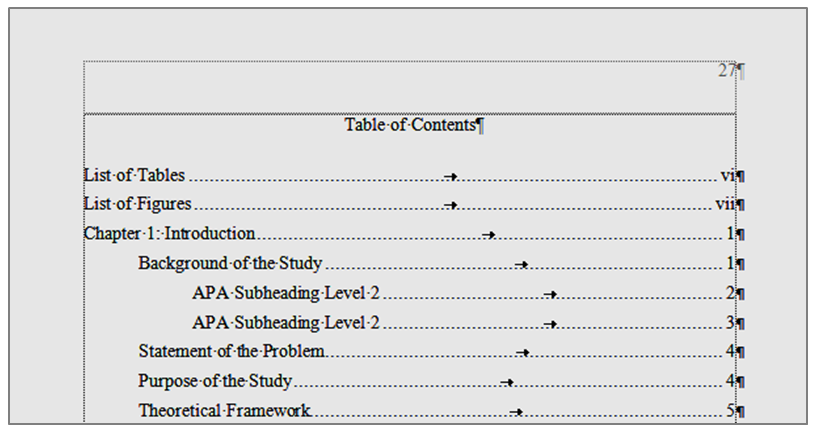

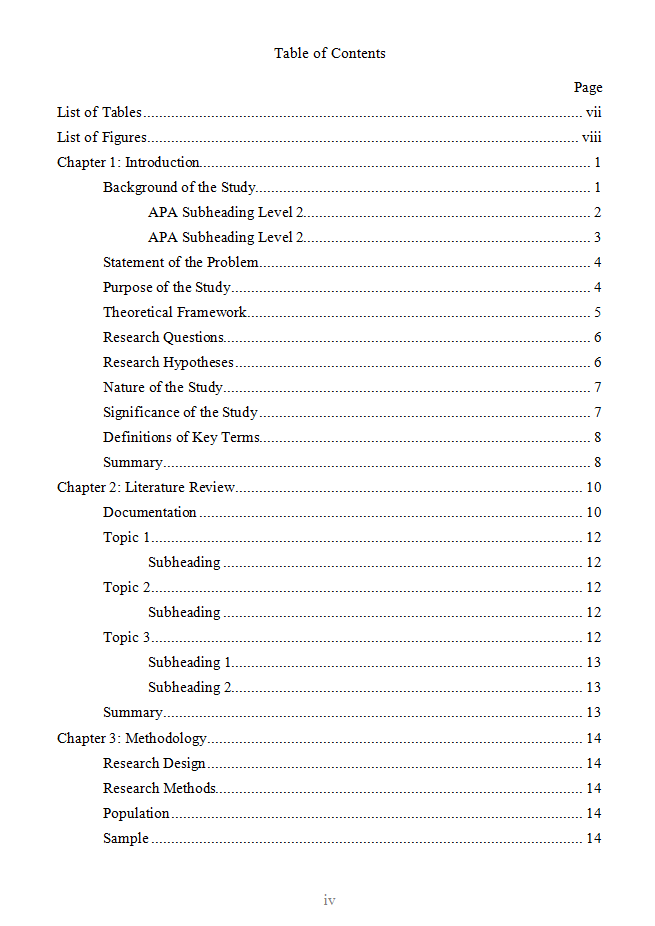

Here’s my suggestion: Work on your outline first. Get it on paper (that means type it up). Figure out what sources support which subsections. Then you can take a nap.

If you need some help, check out my book.