I edit dissertations and proposals, which means I’ve seen many questionnaires and surveys, both proposed and completed. I’m guessing most dissertators think their survey questions are the greatest thing since Survey Monkey. However, sometimes things go wrong, sometimes seriously wrong. Here are ten potential problems you might encounter with your dissertation survey.

By the way, a questionnaire is a set of questions you will ask during your survey. In other words, the questionnaire is the instrument, and survey is your method. You can ask questions in other ways. Right now I’m just talking about questions you might ask using an online survey method.

1. Your survey questions don’t align with your research questions

Before you ask anyone anything, make sure your survey questions align with your research questions, so the data you collect will actually be relevant. There’s no point asking people for data you can’t use. The entire project will be a colossally embarrassing waste of time. You’ll spend months desperately trying to contort your data to address the purpose of your study. At that point, I can understand the temptation to change your research questions to align with your data! (Please, don’t do that. )

TIP: One fail-proof approach is to design your research questions to reflect your theoretical framework, and then build your survey questions to echo your research questions.

2. You can’t find qualified respondents to fill out your questionnaire

Finding qualified people can make you feel like poor old Diogenes lugging around a lantern looking for an honest man. Once you find them, motivating them to participate in your study may turn you into the worst type of academic—the used-car scholar: Please, please, please, be in my study, you can win a free iPad!—and once you sign them up, getting people to answer thoughtfully, thoroughly, and honestly without shaming them is a real challenge, although to be honest, at that point, you won’t care about respect for your subjects. Belmont Schmelmont!*

Assume nobody cares about your study. Unless they have a specific bone to pick about the topic, or they know you and take pity on you, or they just love the research process, participants will not be beating down your door to fill out your online questionnaire. People are busy. They care more about their own problems than they do about helping you achieve your dream of earning a Ph.D. I know, hard to believe, but it’s true.

The main problem with low response rates is that the people who are willing to fill out surveys are often very different from those who are unwilling. The differences between the two groups may include differences in demographic characteristics, as well as personality, attitude, motivations, and preferences. If you base your conclusions on the responses of those who were willing to fill out your survey, and don’t somehow account for the differences compared to those who were unwilling, then your conclusions may be totally off target. This is because your tiny (willing) sample was not representative of the larger (mostly unwilling) population from which it was drawn.

TIP: Design your study with the audience in mind. Before you submit your proposal to your reviewers, do some homework to determine how hard it will be to recruit the sample you need. Make friends with gatekeepers at the institutions where your audience congregates. Locate mailing lists early. Find out what you need to do to get access to the people who need to take your survey. You may need to spend some money.

The worst thing that can go wrong with your dissertation survey: People don’t respond

3. You use online panels whose members are not randomly selected

People sometimes use the word random to indicate something odd happened, like “Wow, I had a totally random morning.” For purposes of devising our sampling plan, though, random has a specific meaning. When we talk about choosing a random sample we mean a probability sample. A random sample means that every person in your population of interest has a known and equal chance of being selected to participate in your study.

All you quantitative dissertators should pay attention to the concepts of probability and randomization. Harnessing these concepts makes you a powerful wizard—in my view, anyway. You may ask, why do we care so much about probability and randomization? Well, if we use some kind of randomization technique to select participants from a group of potential participants (the sampling frame), then we can use probability theory to infer that our sample will most likely represent the whole population from which the sample was drawn. Yowza! Now that’s power!

Unfortunately, we can’t harness the amazing power of probability if we don’t collect data from a randomly selected sample. Research vendors (e.g., Survey Monkey) who manage online panels may be able to recruit a sample from their respondents specifically for your project. The problem is, only people who like to fill out surveys (and win prizes) join these online panels. That means the sample is likely to be heavily biased in favor of a certain type of respondent.

In addition, although the managers of these online panels go to great lengths to validate the quality of their sample, nobody can prove that all those people who claim they are 18 to 24 really are. They might actually be a bunch of bored retirees filling out online surveys for Cheetos coupons. You might whine and say, but don’t I just need a large sample to compensate for problems? My answer is, not if the target audience you need to reach is missing from the sample in the first place.

4. You fail to properly qualify respondents and thus collect unusable data

Some respondents may not be in your sampling frame, but may somehow get a link to your survey. If you don’t build in screening questions up front, you won’t be able to screen out the respondents who don’t qualify to take your survey. Let’s say you want to collect data from females aged 25 to 64 to ask them about their experiences with online dating services.

A couple screening questions will take care of most of the respondents who don’t belong in your sample. Question 1: “Please indicate your gender.” Anyone who clicks “Male” (or “Decline to answer”) will be terminated from the survey. Question 2: “Please indicate which age bracket describes you.” Anyone who clicks “Less than age 25” or “Over age 64” (or “Decline to answer”) will be terminated from the survey. If all goes according to plan, you will be left with a sample of 25- to 64-year-old females.

Of course, without some corroborating information, you have no way of knowing who is telling the truth and who might be lying. The odds are very low that a respondent will lie for your dissertation survey, but a lot depends on your topic. A juicy or controversial topic may attract more respondents who are willing to say they meet your qualifications just to take your survey. You might say wow, cool! Sorry. If you suspect your data are bad, you won’t be able to trust your conclusions. It’s a dismal dissertator who must report that her data were compromised and therefore her entire study is invalid.

5. Your survey questions are vague, misleading, or misspelled

Validate your survey questions before you go live. That means test them on real people, get feedback from them after they answer the questions, and collect and analyze the responses to make sure you get the data you seek. You may need to apply to your IRB to do a pilot study before you get to the main event. I know, it’s a hassle, but the alternative is you spend weeks or months fielding a survey that yields unusable data.

TIP: Ask your screening questions up front to screen out unqualified participants. Ask general questions first, then move to specific questions. Place intrusive (demographic) questions at the end.

TIP: Avoid asking two questions in one. For example, “Please indicate your satisfaction with the course and the teacher.”

TIP: Avoid leading questions. For example, “Given the sad state of the current healthcare system, what actions would you recommend policymakers take in the upcoming year?”

TIP: Use plain language. Give simple instructions. Make sure everything is spelled correctly. I know you want to be an academic scholar, but for your survey questions, write like a normal person—write the way normal people talk. If your respondents are confused about what you mean, they will make up stuff, and you will end up with bad or missing data. This is why we test our questionnaires on real people first.

6. A respondent could click the SUBMIT button more than once

Depending on the software you use to present your online survey, your respondents may not see a “redirect” option that takes them to another URL when the survey is submitted. Other than the message you provide or the generic “Your response has been recorded” message, your respondent won’t see much of anything change. She may not be certain the survey was actually submitted, so she might feel motivated to click SUBMIT again, just in case, because she’s expecting to see something dramatic, like a link to claim her incentive. Survey Monkey sends respondents to a generic Survey Monkey page. As of this writing, Google Form does not.

If respondents click SUBMIT more than once, this error will show up as duplicate rows in your spreadsheet. If you have any open-ended questions, you will quickly realize that the records are duplicates: The odds of two people typing “I had a baloni and cale sanwich for lunch today” are relatively slim.

To fix this error, do not delete the row in the web-based spreadsheet. Actually, you won’t be able to delete a row, but you could delete the data in the row. It’s best not to edit the data in the actual web-based spreadsheet itself. This is your pristine data source, and you don’t want to mess it up. Download the spreadsheet to Excel, create a mirror copy of the data (see details in REASON 17 in my book), and then clean the data by deleting the data only (leave the row intact—don’t delete the row! It’s like retiring a football jersey number—it still exists, but you won’t use it, and nobody else can use it either).

TIP: Make sure your downloaded spreadsheets match row for row, column for column to the web-based spreadsheet. This is important. Rows are records. Each record number is a respondent. In the web-based survey spreadsheet, you can’t delete a row, but in Excel you can. Don’t do it. Make sure the record (row) numbers match the web-based spreadsheet.

7. A respondent could take the survey more than once

Last I heard, Survey Monkey Pro has the capability to track the IP addresses of computers, but that doesn’t mean a respondent can’t use multiple computers or other devices. I don’t think this is common (most people avoid surveys, they don’t go out of their way to take one twice); however, I suppose it could happen. Odds are, though, it won’t happen to you. I think Google Form can now track email and IP addresses, too.

You may spot something fishy in some responses that may lead you to think someone took the survey more than once. Again, responses to open-ended questions may be a tip-off. The responses may not match exactly, but spelling or wording might be the same (“cale sanwich” would be a clue). However, unless there is some monetary reward for taking the survey, this problem should not occur. It’s more likely you’ll have the problem of motivating people to fill out your survey just once, let alone twice.

8. A respondent could enter data incorrectly

For example, someone might type their age as 544 when they meant to type 54. (Darn those smartphones!) For each variable, you’ll be checking for responses that fall outside the expected range. However, if someone typed 54 when they meant to type 45, unless you have another question to corroborate their age, you’ll never catch this error.

Sometimes respondents enter data incorrectly (from their point of view) because the question is confusing or you haven’t offered them a range of choices that includes their preferred response. Most survey questions will offer an “Other” option so people can add their thoughts in a small text box. You might prefer to force them to answer one of the responses you provide, because including responses outside your range introduces all kinds of data analysis and reporting challenges for you. However, if you don’t give people choices, they either won’t answer the question, or they will click randomly, which defeats the purpose of collecting data from them in the first place.

TIP: Again, make sure your questions are clear and that you test them on real people first before you go live with your survey.

9. A respondent could answer the wrong questions

On a paper and pencil survey, this problem is common. Respondents don’t tend to read instructions. They may not see a direction that says, “skip Question 4 if you aren’t attending graduate school online.” They will flail ahead and answer the questions intended for online learners, even if they attend their program entirely onsite. On a web-based survey, using skip logic, you can allow respondents to bypass questions they aren’t qualified to answer.

Mistakes can happen, though. These data entry errors are easy to fix. On your spreadsheet, delete the data entered by all the people who shouldn’t have answered the question. This process is called cleaning the data.

10. A respondent could fail to answer one or more questions

This is by far the most common problem in a survey. Tell me you haven’t skipped over some questions on surveys before! Especially open-ended questions that require us to think, or type, or both. Ugh. Any question that is hard to read, understand, or answer is more likely to be purposely skipped by respondents. Unfortunately, we can’t force respondents to answer our questions (see REASON 21, the chapter on ethical issues, in my book). Respondents sometimes bail before they get to the end, and there’s not a darn thing we can do about it.

If you are missing too much data, your analysis could be seriously jeopardized. You need to have a plan for how you will handle missing data. First, though, write a good set of survey questions! Duh.

What kind of data are missing and what effect could this have on your analysis? If you have a large enough sample, leaving out the missing cases altogether in the analysis of that question might work. But you run the risk that the people who didn’t answer the question are in some important way different from the people who did. Then you’ve got a biased analysis. Bummer.

SPSS lets you evaluate the patterns in missing data to help you figure out if the missing data patterns are random. If they are, you can exclude the cases from the analysis. If it looks like the pattern of missing data is not random, then you have to decide how you will handle the problem. Some researchers have recommended plugging in the mean, although that can lead to biased outcomes (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008). SPSS can generate the missing data for you using several methods (IBM, n.d.).

Final thoughts

Recruiting qualified respondents is hard, and they rarely cooperate, darn it. But few things are more fun for a researcher than asking people what they think about some obscure topic most people could not care less about. It’s not unlike the story of Sisyphus, rolling a boulder up a hill.

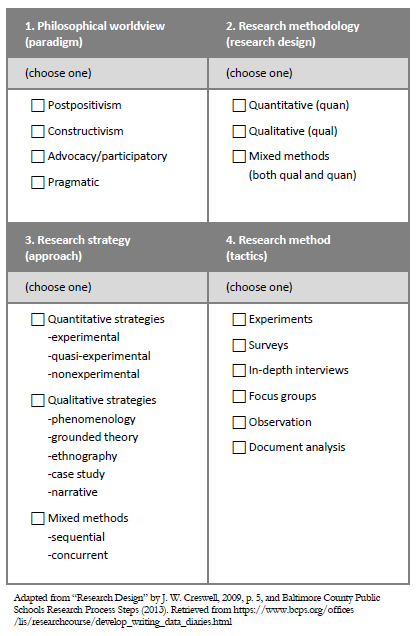

At this point, you are most likely just struggling to get your proposal approved so you can move on to data collection. Whether you are doing quantitative or qualitative research, if you need some help, check out my book.

*The Belmont Report summarizes ethical principles and guidelines for research involving human subjects.

Sources

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Belmont report. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belmont_Report

IBM. (n.d.). Impute missing data values (multiple imputation). Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/SSLVMB_24.0.0/spss/mva/idh_idd_mi_variables.html

Trochim, W. M. K., & Donnelly, J. P. (2008). Research methods knowledge base [3rd ed.]. Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.