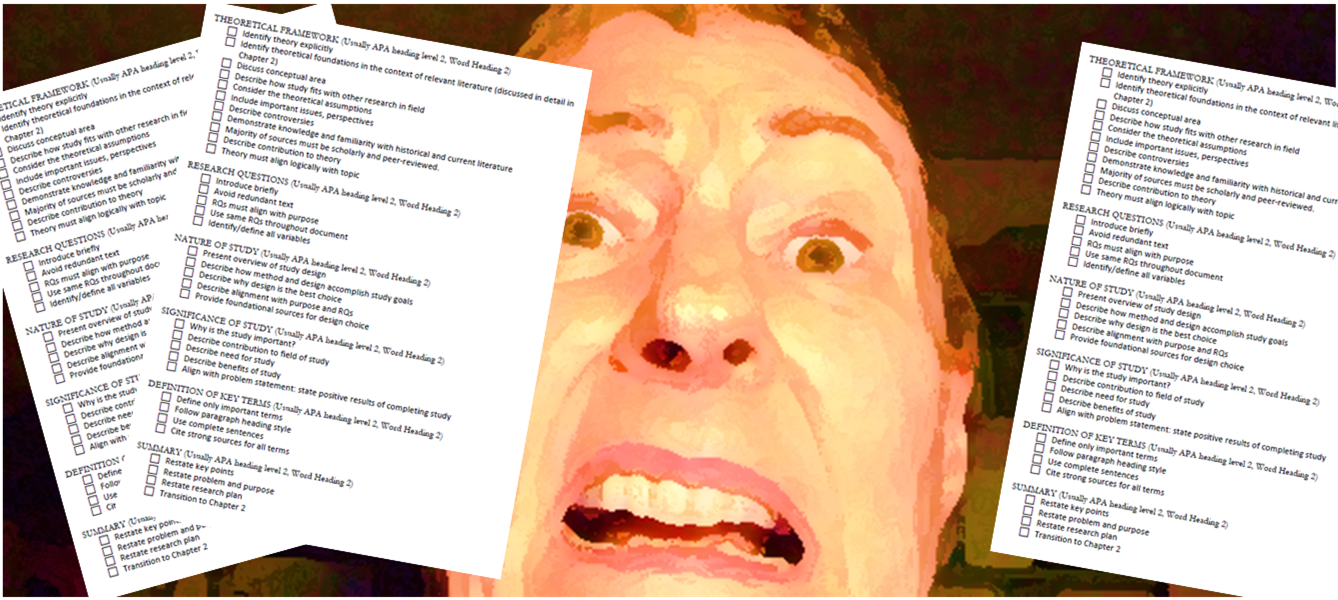

Download my dissertation checklist for free

Despite the photo, I like lists. Checking things off my list gives me the sense of accomplishment that helps me keep going. In fact, I doubt if I would have finished my dissertation without my dissertation checklist.

I’ve updated my dissertation checklist, and now you can download it for free (without registering or anything!) here. Just sneak in and grab it in Word format. Customize it for your own needs. This generic checklist includes many of the elements you need in your dissertation proposal. I also preview the elements you’ll need to include in your dissertation manuscript, after you collect and analyze your data.

The dissertation proposal

A large project like a doctoral research project has many moving parts, one of which is the dissertation. In the social sciences, dissertations are typically five or six chapters, plus some front matter (title page, abstract, acknowledgments, table of contents, lists of tables and figures, maybe a list of abbreviations) and some back matter (generally just the list of references and the appendices).

The first three chapters of a typical dissertation comprise the dissertation proposal. In this and three subsequent blog posts, I describe the sections of a dissertation proposal. Part I covers the front matter of your proposal. Part II covers Chapter 1, the introduction to your study. Part III covers Chapter 2, the basis of your justification for the study, also known as the Literature Review. Part IV focuses on Chapter 3, the blueprint for your research project, usually entitled Methodology. My discussion is generic, based on what I usually see in the dissertations I edit. Not all institutions require the same format. Follow your institutional guidelines.

The dissertation proposal: the front matter

The term front matter refers to all the pages that come before the first page of Chapter 1. Different universities require different elements in the front matter. Sometimes institutional guidelines can be quite strict. Other times they are refreshingly flexible. Here are the typical elements I find in the front matter section of a dissertation proposal.

Title page. Typically, the front matter starts with a title page. At the least, the title page provides the title of the study, the author, the degree, the school, and the date. Some of you will have to add the names and titles of your committee members. Follow your institutional guidelines. They may even have a template you can paste into place and customize for your project.

Abstract. The abstract is the overview or summary of the entire study. For your proposal, include one statement to introduce the topic, followed by the research problem and purpose of the study. Don’t include your research questions—later on, you won’t have room. For your proposal, focus on the problem, purpose, participants, and methods, and keep it short: The typical Abstract in a finished dissertation manuscript is no more than 350 words.

Acknowledgments & Dedication. We all want to acknowledge the people who helped move us along our dissertation journey. You can ignore this page for your proposal—in fact, I recommend that you do. Leave a placeholder (the title and a blank page), and fill it in after you’ve finished and received approval your dissertation manuscript. Then you can thank your mother, your mentors, your spouse, whoever helped you along your journey. I love to edit acknowledgments pages—I can hear the relief, gratitude, and profound weariness in the dissertators’ voices as they thank everyone under the sun. I know the feeling. I’d like to thank my cat, Eddie. An optional Dedication page may follow the Acknowledgments page.

The Table of Contents. Next up is usually the Table of Contents. If you don’t know by now, the Table of Contents (fondly known as the TOC) is an outline of your entire paper, usually to three or four levels of subheadings, depending on how your institution treats chapter headings. Some institutions put chapter headings in a class of their own, separate from the other heading and subheadings. Other institutions treat chapter headings as level 1 headings. Whatever. It matters, but not enough to fret about now. You’ll figure it out when your Chair dings you for not having three (or four) heading levels in your TOC. Argh.

A few dissertators who aren’t afraid of Word styles have figured out that Word can insert an automatic TOC. Most dissertators would probably like that idea, but are terrified of setting up and applying Word styles to their headings, and thus resort to typing their TOCs manually. Oh the humanity. I take a look, cringe, and delete the entire thing, all those pages of spaces, tabs, raggedy page numbers—yep, all gone. Then I proceed to set styles for all those headings and subheadings. I go through the paper, tagging each heading and subheading with the appropriate style. That takes a while, depending on how hard it is to figure out the dissertator’s intentions. Then I insert a TOC, bada boom, it’s done, in about six seconds. That is how you do a TOC.

Every now and then I will edit a paper from some harried dissertator whose institutional guidelines seem hell bent on making it impossible for anyone to get approval. Things in the TOC must line up just so, the k under the j, and indented just this amount, no more and no less. In those rare cases, Word’s automatic TOC feature will only get us partway to the goal. Annoying, but what can we do? I guess we could do some programming in Word, but that’s above my paygrade. Feel free. If the TOC has minute formatting requirements, I insert the TOC, convert it to plain text, and then format it as required, hoping that the dissertator won’t move stuff around and mess up the pagination. That’s a different subject for another day.

To update your TOC, click anywhere in it and press F9 on your function key row, or right-click and choose Update Field. You can update the entire table or just the page numbers.

Lists of Tables and Figures. The Table of Contents is usually followed by the List of Tables and the List of Figures (starting on separate pages). Usually the List of Tables comes first, but actually, I believe the List that should come first is the one that is the longest. Follow your institution’s template.

The magical trick of creating these lists is to use Word’s INSERT CAPTION function. You can insert labels above each table (e.g., Table 1) and below each figure (e.g., Figure 1). Word will generate accurate lists of each. You won’t have to type anything except the table titles and the figure captions. Bada bing. Magic. On rare occasions, I like Word. Making these lists is one of them. To update your list, click anywhere in it and press F9 on your function key row, or right-click and choose Update Field.

List of Abbreviations. Most dissertators don’t include a list of abbreviations, unless they are in the military. Dissertators who are or were in the military usually present an extensive list of acronyms, because that is their common language. If you have a list of abbreviations or acronyms, present it simply and concisely, without definitions. You’ll have a section in Chapter 1 to present your definitions of key terms.

The end of the front matter

When I see the term front matter, for some reason I think of gray matter and then wonder, do I have any left? Uh-oh. Then I think, front matter doesn’t matter, which is just silly—of course, front matter matters, if you are writing a dissertation proposal. How your front matter looks is a huge clue to the quality of the rest of your proposal. For example, if I see that you’ve manually typed your Table of Contents, I know that your comfort level with Word is low. That means I will be on the lookout for other formatting errors, and I will find them. Front matter matters in the sense that this section sets the level of expectation for the three chapters that follow.

The final page of the front matter marks the transition between the preliminary gobble-de-gook (technical term for all that stuff I’ve been talking about) and your actual paper. The front matter prepares your reader (or reviewer) for the proposal that follows. That means you need a dividing line between the two sections. We accomplish this in Word using a section break.

That means, at the end of the final page in your front matter, there should be a NEXT PAGE SECTION BREAK. This is the crucial section break in most dissertations. You can have more, and you may be required to have more, but if the pagination of the front matter changes on page 1 of Chapter 1, you’ll need at least this one section break or you’re a goner. You’ll find this essential section break in the little section break boutique under the PAGE LAYOUT Ribbon.

The section break tells Word that the formatting in section 2 can be different from the formatting in section 1. That’s great, because quite often the page number format changes from lowercase Roman numerals to Arabic numerals, don’t ask me why. If you ever accidentally deleted a section break and cried out in horror as your margins, page numbers, headers, and footers went wonky, you know what I am talking about. Quick, CONTROL Z!

If you can’t see your section breaks, it’s not your eyes. Turn on the “nonprinting characters” by clicking the SHOW/HIDE button on your Home Ribbon. Voila! Suddenly the extent of your crappy keyboarding ability becomes apparent. Yikes! Where did all those extra spaces and tabs come from? Yep. You tried to align things using spaces, didn’t you? Whoopsy.

In the next blog post, I dig deep under the hood of Chapter 1 to reveal the surprising number of essential elements, all of which you will need if you want to get your proposal approved.

I’ve written the book I wished I had had when I was sweating over my proposal, watching the clock ticking and thinking, hmmmm, failure is apparently an option after all. I wanted simple, practical advice from someone who had been in my shoes, someone who didn’t throw more academic jargon at me, but shared real stories to give me insight into the obstacles that were holding me back. I wrote the book I didn’t have when I could have really used the help.

I’ve written the book I wished I had had when I was sweating over my proposal, watching the clock ticking and thinking, hmmmm, failure is apparently an option after all. I wanted simple, practical advice from someone who had been in my shoes, someone who didn’t throw more academic jargon at me, but shared real stories to give me insight into the obstacles that were holding me back. I wrote the book I didn’t have when I could have really used the help.