(Excerpt from my new book Applying Theory, Chapter 1)

How I used theory today—Scenario 1

Today was a day much like any other. I woke with my cat sitting on my chest. My first thought was, why does he always do that? To answer my question, I tried to come up with some possible explanations.

- He’s out of food.

- He’s bored.

- He barfed and felt an urgent need to notify me so I can fulfill my duty to clean it up.

I began to test each explanation. Moving gingerly toward the kitchen, I checked all nearby rugs but found no barf or hairballs. Okay, so that couldn’t explain his behavior. Next, I checked his bowl: He had plenty of kibbles, so that wasn’t the reason for his behavior. Of my three possible explanations, the one that made sense was he was bored.

However, it is possible my cat knows that if I don’t get up by a certain hour I feel like such a slacker I am likely to bury my head under the covers for a couple more hours to avoid facing the day. My cat could be smart like that. If you have a cat, you know what I mean. Maybe he’s trying to tell me something. I made a mental note to consult a cat whisperer.

Can you guess what was I doing in that scenario? I was generating and testing theory! I asked questions, and my brain offered some possible explanations, which I could then test to discern the best answer for the question.

How I used theory today—Scenario 2

Here’s another scenario. As I waited for the teakettle to boil, I noticed it seemed chilly in the kitchen, especially around my feet. Why was it so cold? My mind immediately conjured several possible explanations.

- Cold air settles near the floor.

- The east wind blowing against the side of the house could have sucked all the warmth out of the room.

- The thermostat could be broken again.

Which explanation was correct? First, the air under the ceiling was likely warmer, compared to the air around my feet. The evidence I have for that explanation is my cat’s preference for sleeping on the top of his six-foot tall cat tree on cold days.

If this explanation was correct, what could I do about cold air settling by my feet? I couldn’t easily build a similar structure for myself (I’m way too old to climb trees, indoors or out), but maybe I could run a fan to circulate the air in the kitchen . . . so that the air was uniformly cold on my entire body, not just on my feet. Right, great solution.

What about that east wind? What could I do if that was the explanation? I couldn’t stop the wind from blowing, but I could put plastic over the windows to help block the cold drafts that seeped around and through the glass. Okay, done.

Finally, I could check the thermostat to make sure it was working properly. If it was, I could crank it up, never mind the heating bills. If the thermostat wasn’t working, I could call the property managers. Alternatively, I could put on more layers (too many as it is) or I could do jumping jacks to warm up (unlikely).

Again, I was generating and testing theory. I asked questions, and my brain offered some possible explanations, which I could then test to discern the best answer for the question.

How about that! Two theories generated before I even had my tea! Thus the day goes.

What about academic theory?

Not all researchers would consider these explanations academic theories. I admit, I am using the term theory in an everyday sense. As you will see, theory comes in many sizes, from micro to macro, from practical to abstract. Trying to conjure reasons why my cat behaves the way he does is an example of a microtheory, interesting only to me. I could expand the question to encompass all cat behavior; that would be moving toward a macro theory. If I were ambitious (which I’m not), I could use my cat’s behavior to try to generate an all-encompassing macrotheory of everything. Right, wish me luck with that.

Think about the links between observation, question, explanation, research, and practice. All five elements connect to create the knowledge base we need to solve problems. However, notice that embedded in our theoretical musings are our cultural circumstances—in my case, single, middle-aged White American female with one cat. Whatever theories we may derive in our academic research will inevitably reflect our cultural identities, as well as those of our readers (DiMaggio, 1995).

Cultural background notwithstanding, I hope you can see that we all use theory, big and small, all the time. I wrote Applying Theory to help you be conscious about it, so you can apply theory like a scholar, finish your dissertation, and earn your degree.

How did you use theory today?

References

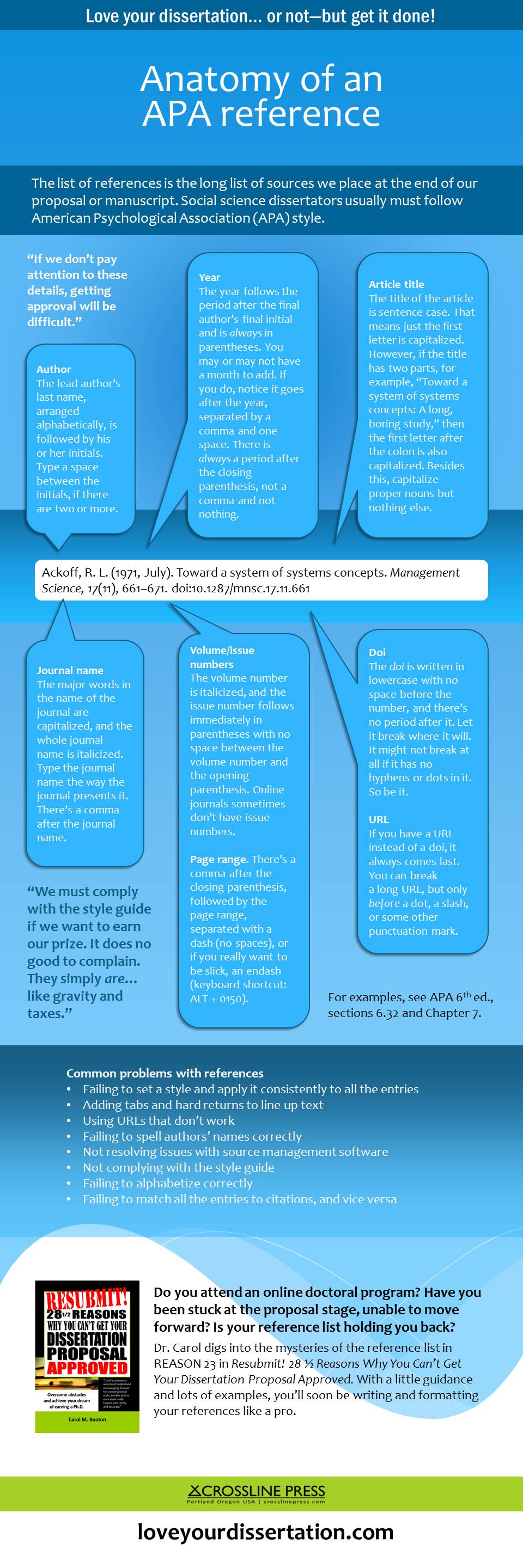

DiMaggio, P. J. (1995). Comments on “What theory is not.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(3), 391–397. doi:10.2307/2393790

Applying Theory

Dissertators often struggle to choose and apply a theoretical framework to their research projects. In this helpful guide, I offer suggestions from my own experience. In addition, I reveal how other dissertators have applied theory successfully and earned their doctorates.

Written in a friendly, nonscholarly manner, I demystify the challenges of applying academic theory to a research project. You will learn that theory is nothing to fear—in fact, we all use theory all the time! With the help of this powerful little book, you will learn to master theory and achieve your dream of earning your Ph.D. Learn more.

Print version

Resubmit! 28 ½ Reasons Why You Can’t Get Your Dissertation Proposal Approved

This comprehensive book is the missing link for dissertators who have struggled to get their proposals approved. This indispensable book bulges with insights, suggestions, examples, diagrams, and practical tips, written especially for the online dissertator who may receive little support during the proposal process.

I present solutions to address twenty-eight potential reasons why you might be struggling to get your proposal approved. For example, you will learn how to write a clear problem statement, devise research questions and hypotheses, and align the elements of the proposal to facilitate speedy approval. I unlock the mysteries of Word and Excel to show you specifically how to use these tools for your proposals. Over 200 tables and figures show you exactly what to do. As a bonus, you will learn how to design a web-based survey and make a plan for fielding and analyzing the data. In this book, I cover it all to help you overcome obstacles and finish your dissertation. Learn more.

Free templates and worksheets are available here.

Print version

Kindle version